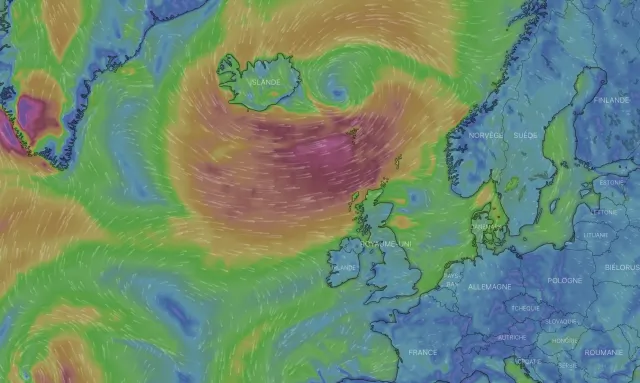

On the water, the conditions were not helping, once again. "Things weren't easing at all, it was a hassle for those in the race and complicated for those who had arrived to stay in their bubble of concentration,” sighs Francis Le Goff. Gradually, an idea begins to gain consensus: stop the race at this gate of Iceland. It would be recorded late Friday evening, a "wise decision for the safety of sailors,” according to Laura Le Goff.

“Restarting the race would have been complex and we had no guarantee that this 2nd leg would be a sporting performance in itself and would not turn into a delivery trip,” explains race director Le Goff. “However, we also had to highlight what the skippers had already done, this very committed, very intense regatta. By making this stop, we were also keen to highlight the battle that had taken place since the start."

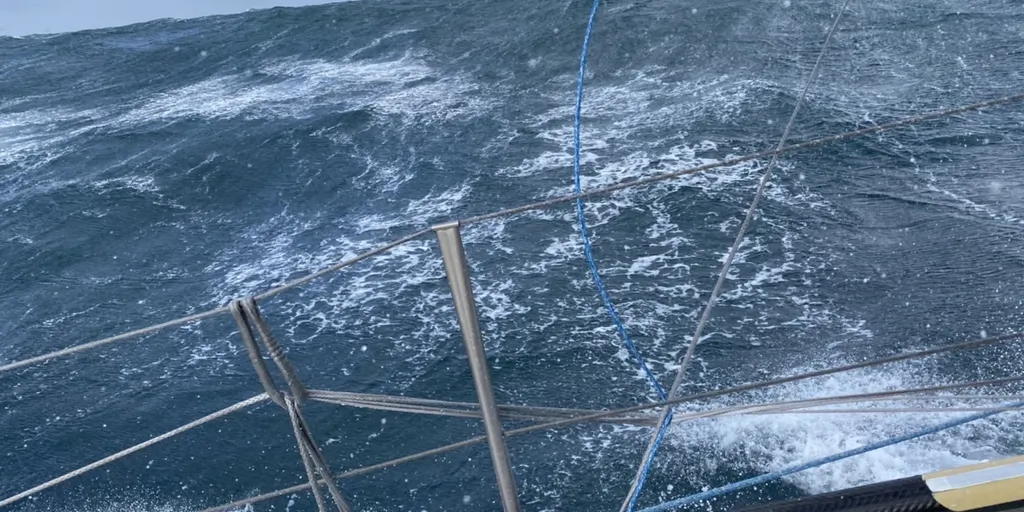

The exceptional harshness of the conditions

Saturday night, when the decision was formalized, Charlie Dalin was named the winner. "I was still working on the course for a possible new start," explains Dalin. “It was special to learn that at anchor!”

The hours that followed confirmed the knockout caused by the depression, which was particularly violent when approaching the finish in heavy upwind sailing. The damage was increasing in the fleet: mainsails torn for Isabelle Joschke (MACSF) and Giancarlo Pedote (Prysmian Group), heavily damaged sail set for Conrad Colman (Imagine), serial problems for Kojiro Shiraishi (DMG MORI GLOBAL ONE), and a damaged hydrogenerator for Romain Attanasio (Fortinet-Best Western). "I thought I would never cross the finish line,” explains an exhausted Attanasio. "It was the hardest thing I've done on a boat,” Éric Bellion (Eric Bellion, COMME UN SINGLE HOMME Powered by ALTAVIA) concurred.

Manu Cousin (SETIN Group) turned back, Isabelle Joschke, Arnaud Boissières and Denis Van Weynbergh (Biarritz Laboratories) – who injured his thigh and lost a rudder – decided to retire. "That says a lot about the exceptional harshness of the conditions,” says Château. “There have been very few offshore races where three boats retired less than 50 miles from the finish.”

"I have never faced such harsh conditions," explains Fabrice Amedeo, who saw 62 knots on hs anemometer. The sailors spoke of "dangerous conditions" (Alan Roura, Hublot), of "particularly intense rhythm,” of their boat that “leaned at 90°" (Eric Bellion, COMME UN SEUL HOMME Powered by ALTAVIA).

Crossing the line has the value of deliverance. On their boats tossed about by the elements, the Icelandic coast offered itself as a reward. Above all, they could finally breathe. The pressure falls and everyone realizes what they survived. It's time for tears, too. "I cried like a kid," says Arnaud Boissières. "I'm so tired that I'm becoming a little more emotionally fragile," admits Giancarlo Pedote. Like a cry from the heart, Amedeo sums up the thoughts of the entire fleet: "We're tired of it…to come here!" For now it is time to rest, recuperate and return to Les Sables d'Olonne. Guirec Soudée (Freelance.com), who knows a lot about the subject, is sure of his experience: "This race was a great adventure.” And these modern-day adventurers have just added a new piece of bravery to their memories.